A Comprehensive Guide to Test-First Development with Redux, React, and Immutable

Update 2016-02-24: Updated react-router to 2.0.0. In tests, replaced use of deprecated setProps() with ReactDOM.render(). Also now using the react-addons-test-utils package so that no imports of 'react/addons' are needed anywhere.

Update 2015-11-06: Updated to the new Babel 6 release. The Babel packages we need to install are now a bit different, and an additional "babel" section is needed in the package.json in both projects.

Update 2015-10-09: Updated to React 0.14, React Router 1.0.0 RC3, and jsdom 6.x. The changes include:

- Installing and using React and ReactDOM separately.

- Using the PureRenderMixin from a separate NPM package.

- Changing the way the routes are set up in

index.jsx - Changing the way the current route's contents are populated into

App.jsx - Removing the

getDOMNode()calls in unit tests, as the test helpers now directly return the DOM nodes.

Update 2015-09-19: Clarified which version of the React Router is used. Various other small fixes and improvements. Thanks to Jesus Rodriguez and everyone who has been suggesting fixed in the comments!

Redux is one of the most exciting things happening in JavaScript at the moment. It stands out from the landscape of libraries and frameworks by getting so many things absolutely right: A simple, predictable state model. An emphasis on functional programming and immutable data. A tiny, focused API... What's not to like?

Redux is a very small library and learning all of its APIs is not very difficult. But for many people, it creates a paradigm shift: The tiny amount of building blocks and the self-imposed limitations of pure functions and immutable data may make one feel constrained. How exactly do you get things done?

This tutorial will guide you through building a full-stack Redux and Immutable-js application from scratch. We'll go through all the steps of constructing a Node+Redux backend and a React+Redux frontend for a real-world application, using test-first development. In our toolbox will also be ES6, Babel, Socket.io, Webpack, and Mocha. It's an intriguing stack, and you'll be up to speed with it in no time!

Table of Contents

- Table of Contents

- What You Will Need

- The App

- The Architecture

-

The Server Application

- Designing The Application State Tree

- Project Setup

- Getting Comfortable With Immutable

- Writing The Application Logic With Pure Functions

- Introducing Actions and Reducers

- A Taste of Reducer Composition

- Introducing The Redux Store

- Setting Up a Socket.io Server

- Broadcasting State from A Redux Listener

- Receiving Remote Redux Actions

-

The Client Application

- Client Project Setup

- React and react-hot-loader

- Writing The UI for The Voting Screen

- Writing The UI for The Results Screen And Handling Routing

- Getting Data In from Redux to React

- Setting Up The Socket.io Client

- Receiving Actions From The Server

- Dispatching Actions From React Components

- Sending Actions To The Server Using Redux Middleware

- Exercises

What You Will Need

This tutorial is going to be most useful for developers who know how to write JavaScript aplications. We'll be using Node, ES6, React, Webpack, and Babel, so if you have some familiarity with these tools, you'll have no trouble following along. Even if you don't, you should be able to pick up the basics as we go.

If you're looking for a good introduction to webapp development with React, Webpack, and ES6, I suggest taking a look at the SurviveJS books.

In terms of tools, you'll need to have Node with NPM installed and your favourite text editor ready to go, but that's pretty much it.

The App

We'll be developing an application for organizing live votes for parties, conferences, meetings, and other gatherings of people.

The idea is that we'll have a collection of things to vote from: Movies, songs, programming languages, Horse JS quotes, anything. The app will put them against each other in pairs, so that on each round people can vote for their favorite of the pair. When there's just one thing left, that's the winner.

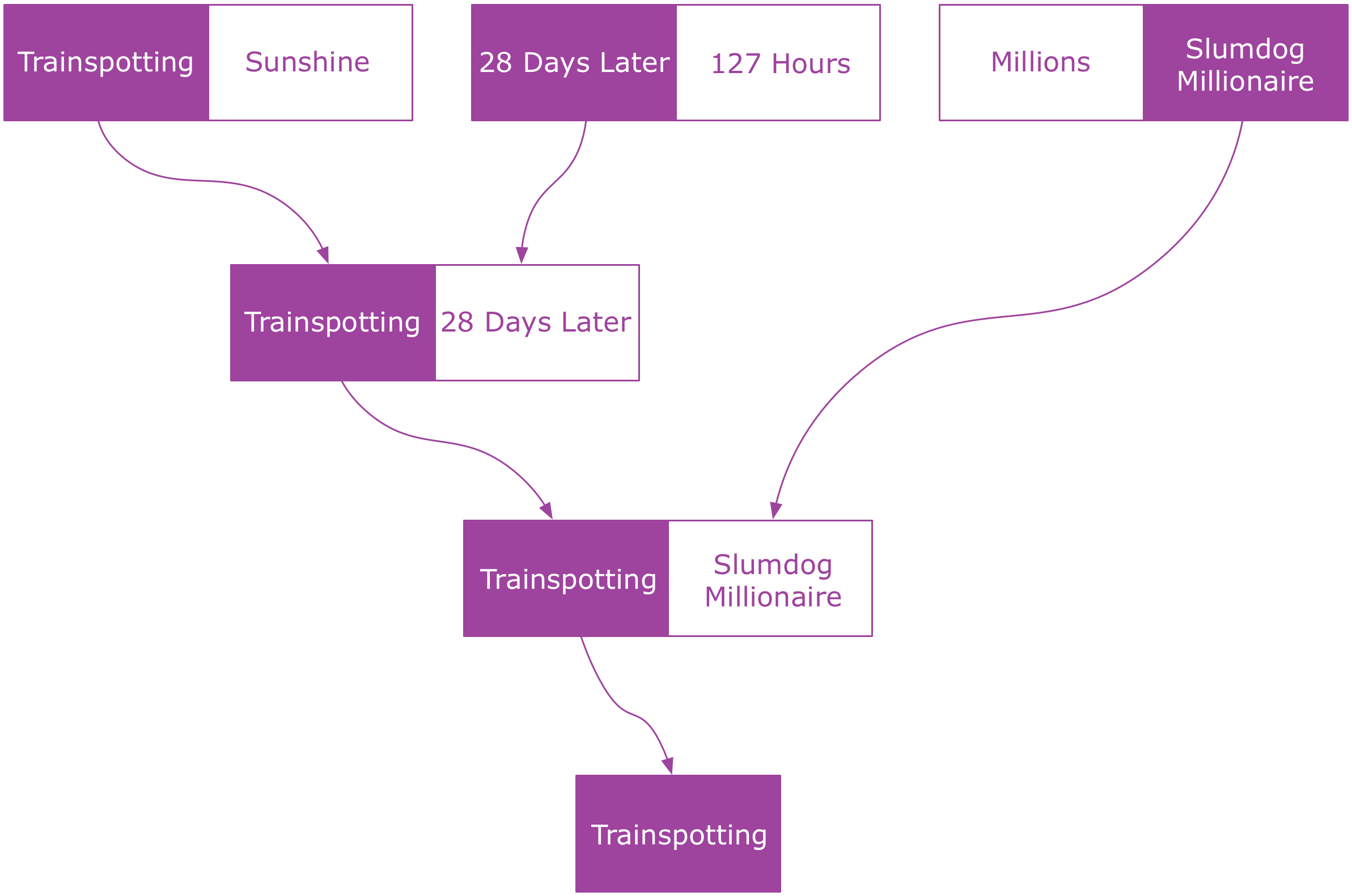

For example, here's how a vote on the best Danny Boyle film could go:

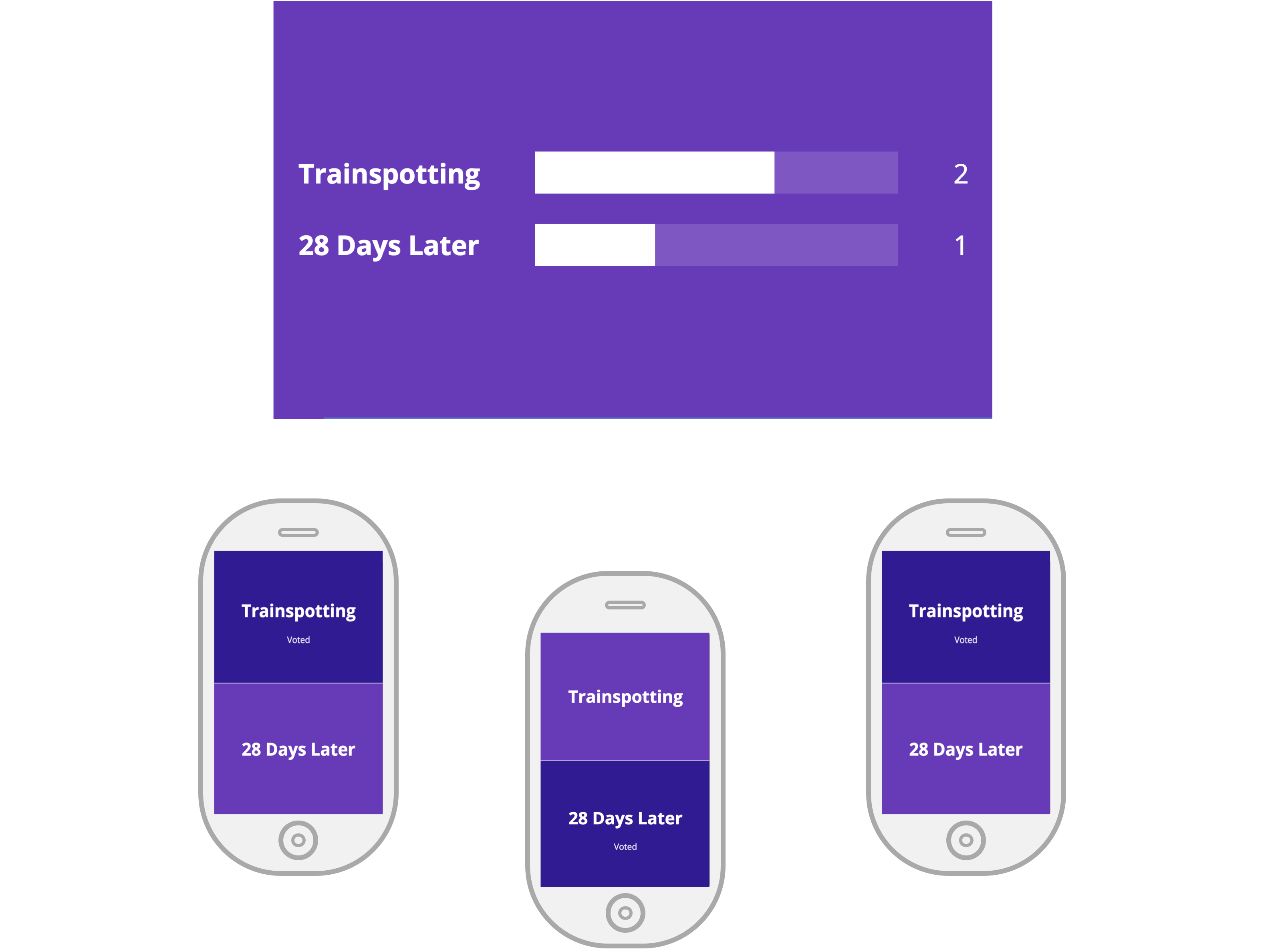

The app will have two separate user interfaces: The voting UI can be used on a mobile device, or anything else that has a web browser. The results UI is designed to be beamed on a projector or some other large screen. It'll show the results of the running vote in real time.

The Architecture

The system will technically consist of two applications: There's a browser app we'll make with React that provides both the user interfaces, and a server app we'll make for Node that handles the voting logic. Communication between the two will be done using WebSockets.

We're going to use Redux to organize the application code both on the client and on the server. For holding the state we'll use Immutable data structures.

Even though there'll be a lot of similarity between the client and server - both will use Redux, for example - this isn't really a universal/isomorphic application and the two won't actually share any code.

It'll be more like a distributed system formed by apps that communicate by passing messages.

The Server Application

We're going to write the Node application first and the React application after that. This will let us concentrate on the core logic before we start thinking about the UI.

As we create the server app, we'll get acquainted with Redux and Immutable, and will see how an application built with them holds together. Redux is most often associated with React applications, but it really isn't limited to that use case. Part of what we're going to learn is how useful Redux can be in other contexts as well!

I recommend following the tutorial by writing the app from scratch, but if you prefer you can grab the code from GitHub instead.

Designing The Application State Tree

Designing a Redux app often begins by thinking about the application state data structure. This is what describes what's going on in your application at any given time.

All kinds of frameworks and architectures have state. In Ember apps and Backbone apps, state is in Models. In Angular apps, state is often in Factories and Services. In most Flux implementations, it is in Stores. How does Redux differ from these?

The main difference is that in Redux, the application state is all stored in one single tree structure. In other words, everything there is to know about your application's state is stored in one data structure formed out of maps and arrays.

This has many consequences, as we will soon begin to see. One of the most important ones is how this lets you think about the application state in isolation from the application's behavior. The state is pure data. It doesn't have methods or functions. And it isn't tucked away inside objects. It's all in one place.

This may sound like a limitation, especially if you're coming to Redux from an object-oriented background. But it actually feels kind of liberating because of the way it lets you concentrate on the data and nothing but the data. And if you spend a little bit of time designing the application state, pretty much everything else will follow.

This is not to say that you always design your entire state tree first and then the rest of the app. Usually you end up evolving both in parallel. However, I find it quite helpful to have an initial idea of what the state tree should look like in different situations before I start coding.

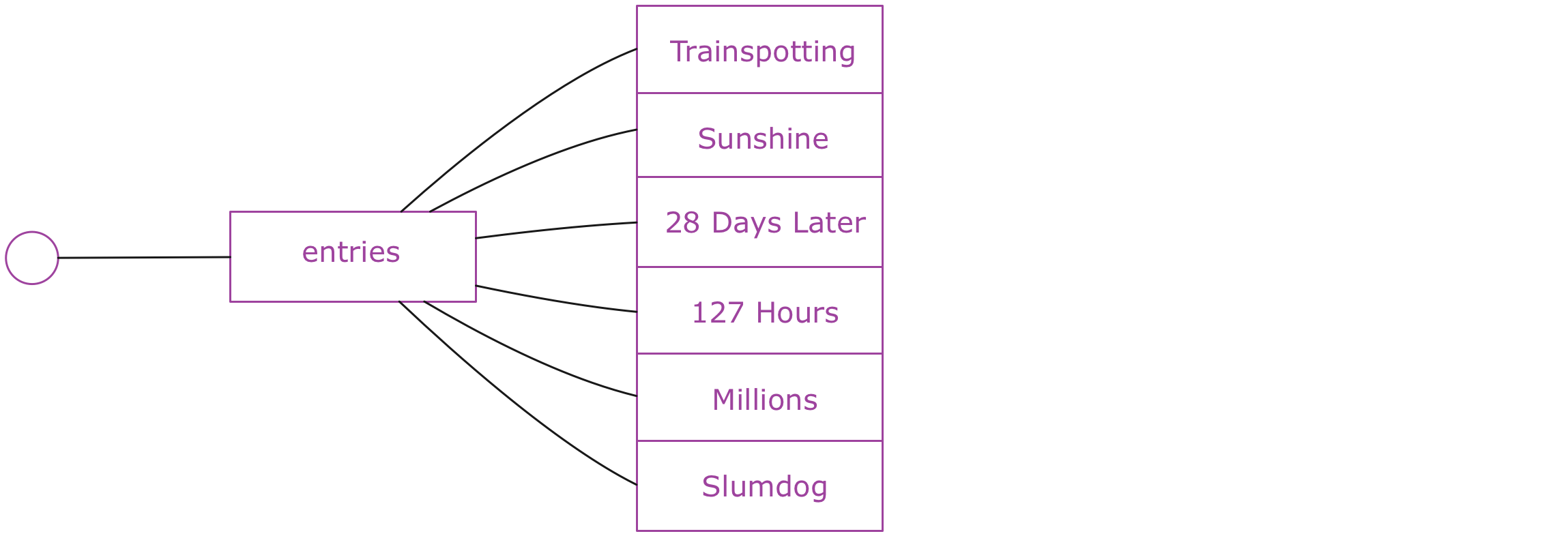

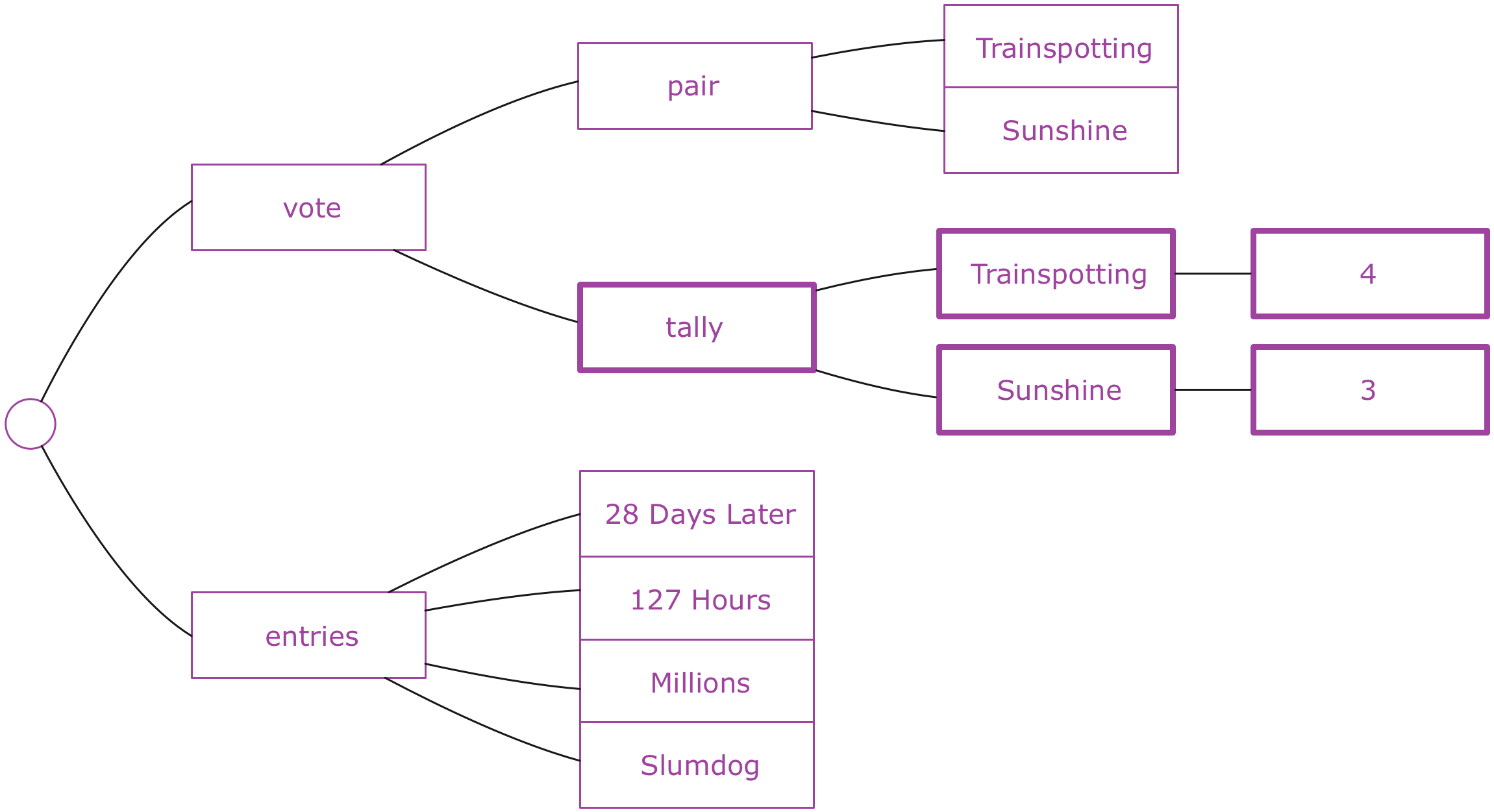

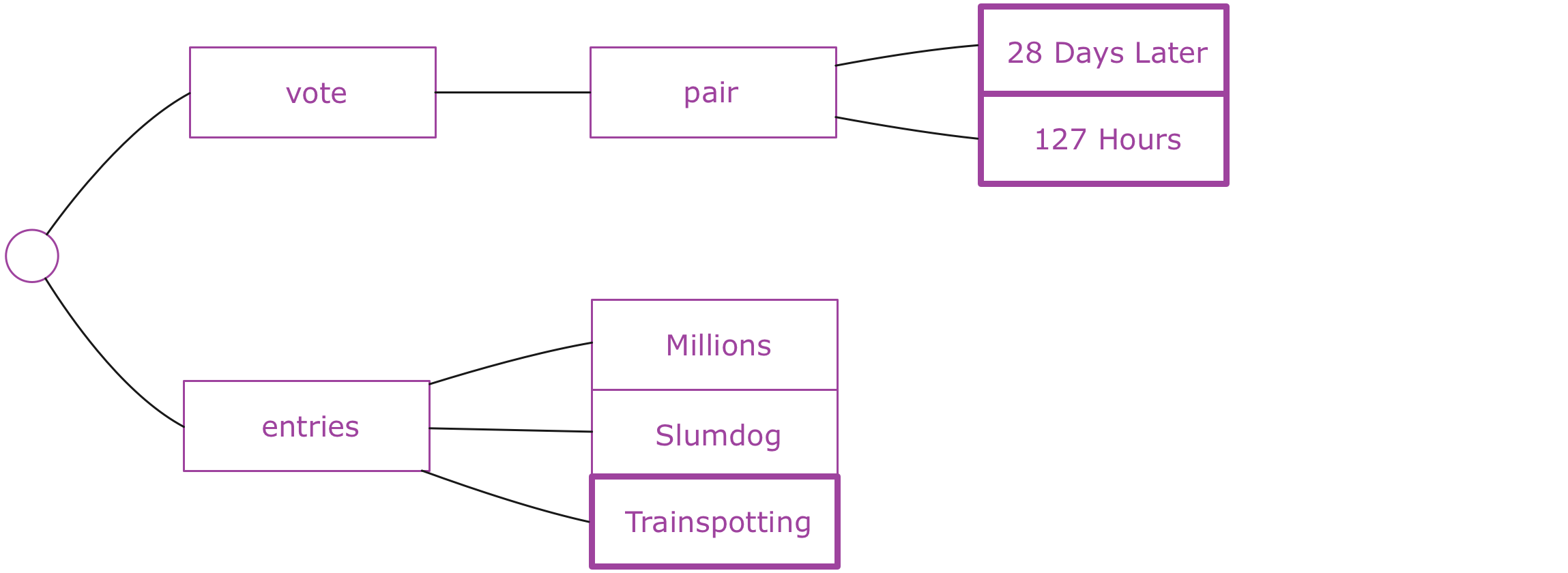

So, let's look at what the state tree of our voting app might be. The purpose of the app is to vote on a number of items (movies, bands, etc.). A reasonable initial state for the app might be just the collection of items that will be voted on. We'll call this collection entries:

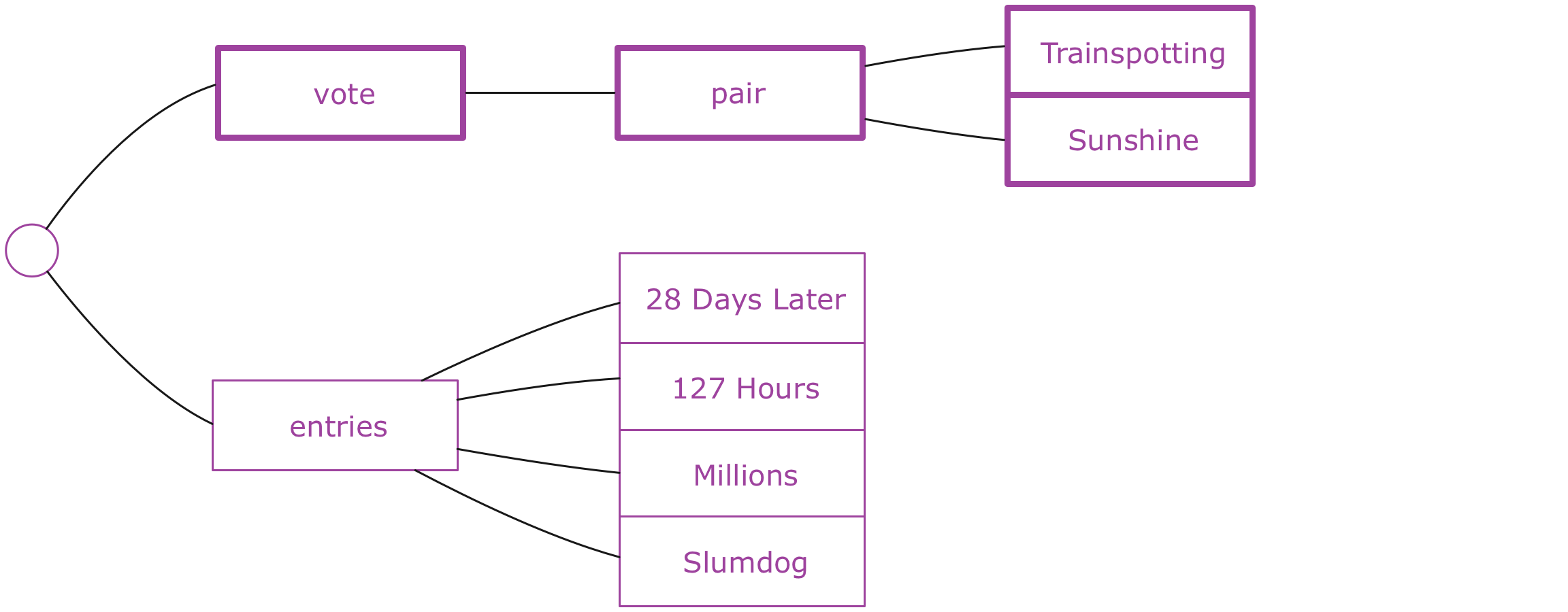

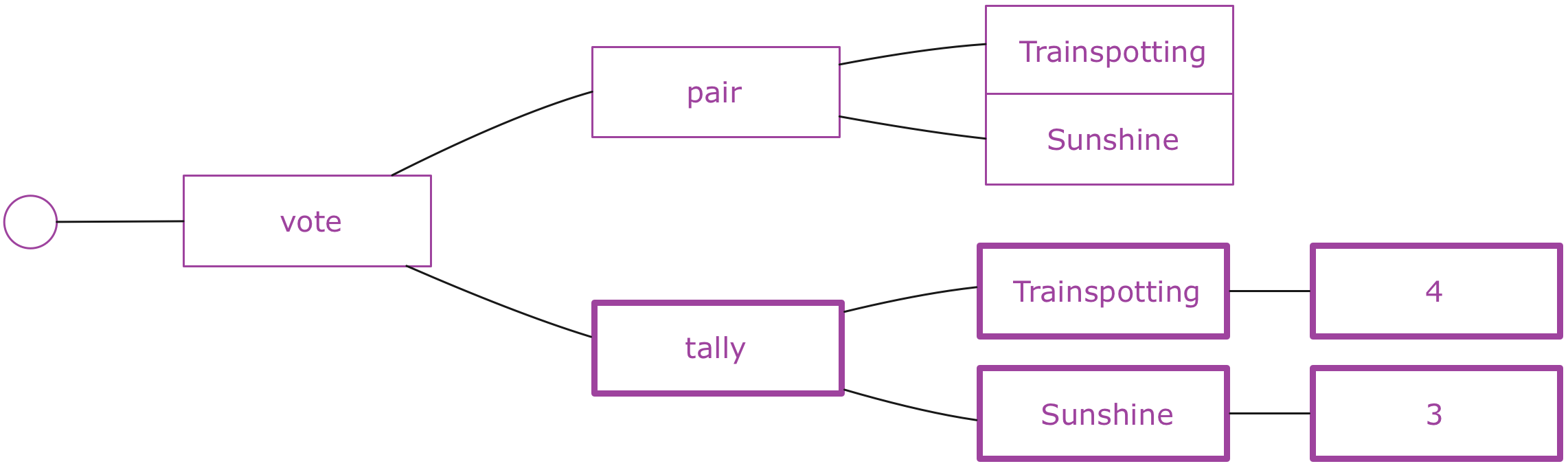

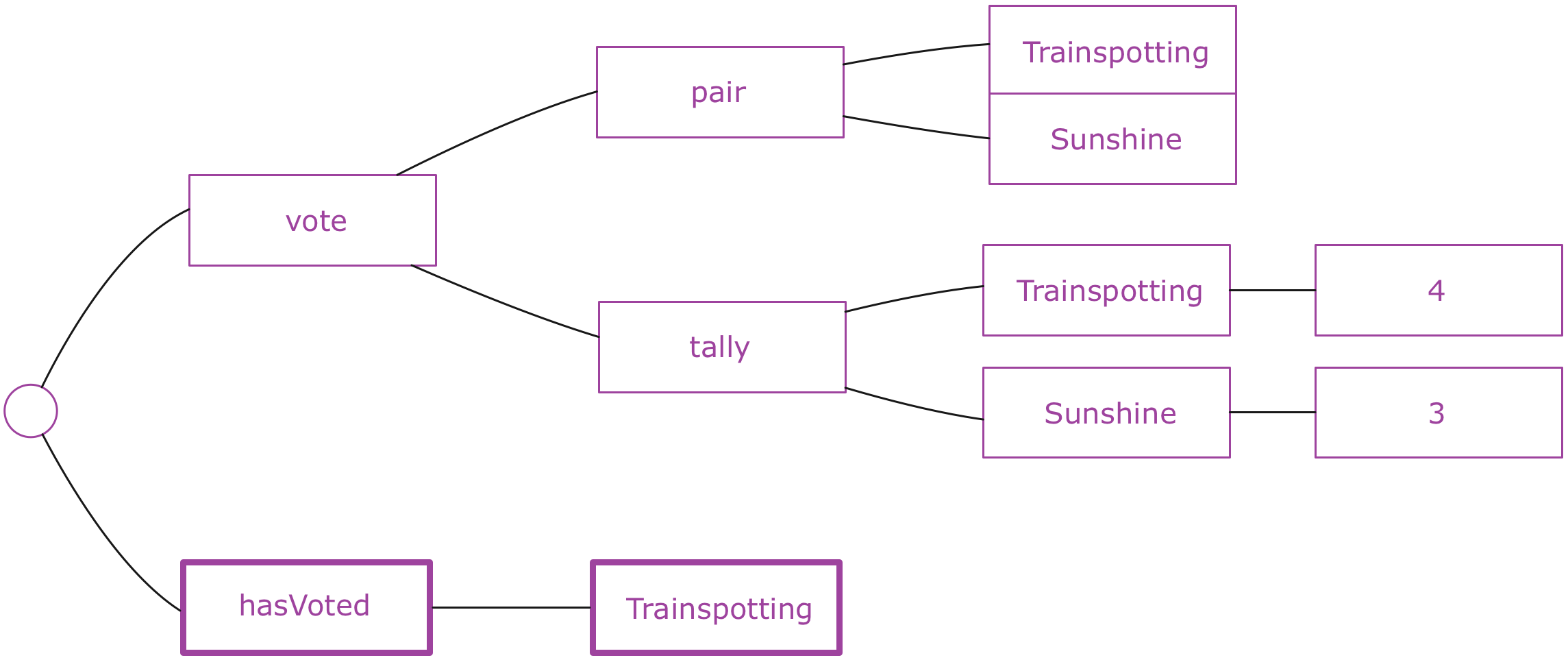

Once the first vote has begun, there should be some way to distinguish what is currently being voted on. In this state, there might be a vote entry in the state, which holds the pair of items currently under vote. The pair should probably also be taken out of the entries collection:

After the votes have started coming in, the tally of votes should be stored as well. We can do that with another data structure inside the vote:

Once a vote is done, the losing entry is thrown away and the winning entry is back in entries, as the last item. It will later be voted against something else. The next two entries will then also have been taken under vote:

We can imagine these states cycling as long as there are entries left to vote on. At some point there's going to be just one entry left though. At that point, it can be declared as the winner and the vote will be over:

This seems like a reasonable design to get started with. There are many different ways to design the state for these requirements, and this might not be the optimal one. But that doesn't really matter. It just needs to be good enough to get started. The important thing is that we have formed a concrete idea of how the application will carry out its duties. That's before we've even thought about any of the code!

Project Setup

It's time to get our hands dirty. Before we do anything else, we need to create a project directory and initialize it as an NPM project:

mkdir voting-server

cd voting-server

npm init -y

This results in a directory with the single file package.json in it.

We're going to be writing our code in ES6. Altough Node supports many ES6 features starting at version 4.0.0, it still doesn't support modules, which we want to use. We'll need to add Babel to the project, so that we can use all the ES6 features we want and transpile the code to ES5:

npm install --save-dev babel-core babel-cli babel-preset-es2015

Since we'll be writing a bunch of unit tests, we'll also need some libraries to write them with:

npm install --save-dev mocha chai

Mocha is the test framework we'll be using and Chai is an assertion/expectation library we'll use inside our tests to specify what we expect to happen.

We'll be able to run tests with the mocha command that we have under node_modules:

./node_modules/mocha/bin/mocha --compilers js:babel-core/register --recursive

This command tells Mocha to recursively find all tests from the project and run them. It uses Babel to transpile ES6 code before running it.

It'll be easier in the long run to store this command in our package.json:

"scripts": {

"test": "mocha --compilers js:babel-core/register --recursive"

},

Another thing we need to do is enable Babel's ES6/ES2015 language support. It's done by activating the babel-preset-es2015 package that we already installed. We just need to add a "babel" section to package.json:

"babel": {

"presets": ["es2015"]

}

Now we can just run the tests with the npm command:

npm run test

Another command called test:watch will be useful for launching a process that watches for changes in our code and runs the tests after each change:

"scripts": {

"test": "mocha --compilers js:babel-core/register --recursive",

"test:watch": "npm run test -- --watch"

},

One of the first libraries we're going to be using is Facebook's Immutable, which provides a number of data structures for us to use. We're going to start discussing Immutable in the next section, but for now let's just add it to the project, along with the chai-immutable library that extends Chai to add support for comparing Immutable data structures:

npm install --save immutable npm install --save-dev chai-immutable

We need to let plug in chai-immutable before any tests are run. That we can do in a little test helper file, which should create next:

import chai from 'chai';

import chaiImmutable from 'chai-immutable';

chai.use(chaiImmutable);

Then we need to have Mocha require this file before it starts running tests:

"scripts": {

"test": "mocha --compilers js:babel-core/register --require ./test/test_helper.js --recursive",

"test:watch": "npm run test -- --watch"

},

That gives us everything we need to get started.

Getting Comfortable With Immutable

The second important point about the Redux architecture is that the state is not just a tree, but it is in fact an immutable tree.

Looking at the trees in the previous section, it might at first seem like a reasonable idea to have code that changes the state of the application by just making updates in the tree: Replacing things in maps, removing things from arrays, etc. However, this is not how things are done in Redux.

A Redux application's state tree is an immutable data structure. That means that once you have a state tree, it will never change as long as it exists. It will keep holding the same state forever. How you then go to the next state is by producing another state tree that reflects the changes you wanted to make.

This means any two successive states of the application are stored in two separate and independent trees. How you get from one to the next is by applying a function that takes the current state and returns a new state.

And why is this a good idea? Well, the first thing that people usually mention is that if you have all your state in one tree and you do these kinds of non-destructive updates, you can hold on to the history of your application state without doing much extra work: Just keep a collection of the previous state trees around. You can then do things like undo/redo for "free" - just set the current application state to the previous or next tree in the history. You can also serialize the history and save it for later, or send it to some storage so that you can replay it later, which can be hugely helpful when debugging.

However, I'd say that even beyond these extra features, the most important thing about immutable data is how it simplifies your code. You get to program with pure functions: Functions that take data and return data and do nothing else. These are functions that you can trust to behave predictably. You can call them as many times as you like and their behavior won't change. Give them the same arguments, and they'll return the same results. They're not going to change the state of the world. Testing becomes trivial, as you don't need to set up stubs or other fakes to "prepare the universe" before you call something. It's just data in, data out.

Immutable data structures are the material we'll build our application's state from, so let's spend some time getting comfortable with it by writing some unit tests that illustrate how it all works.

If you're already comfortable with immutable data and the Immutable library, feel free to skip to the next section.

To get acquainted with the idea of immutability, it may be helpful to first talk about the simplest possible data structure: What if you had a "counter" application whose state was nothing but a single number? The state would go from 0 to 1 to 2 to 3, etc.

We are already used to thinking of numbers as immutable data. When the counter increments, we don't mutate a number. It would in fact be impossible as there are no "setters" on numbers. You can't say 42.setValue(43).

What happens instead is we get another number, which is the result of adding 1 to the previous number. That we can do with a pure function. Its argument is the current state and its return value will be used as the next state. When it is called, it does not change the current state. Here is such a function and a unit test for it:

import {expect} from 'chai';

describe('immutability', () => {

describe('a number', () => {

function increment(currentState) {

return currentState + 1;

}

it('is immutable', () => {

let state = 42;

let nextState = increment(state);

expect(nextState).to.equal(43);

expect(state).to.equal(42);

});

});

});

The fact that state doesn't change when increment is called should be obvious. How could it? Numbers are immutable!

You may have noticed that this test really has nothing to do with our application - we don't even have any application code yet!

The test is just a learning tool for us. I often find it useful to explore a new API or technique by writing unit tests that exercise the relevant ideas, which is what we're doing here. Kent Beck calls these kinds of tests "Learning Tests" in his original TDD book.

What we're going to do next is extend this same idea of immutability to all kinds of data structures, not just numbers.

With Immutable's Lists, we can, for example, have an application whose state is a list of movies. An operation that adds a movie produces a new list that is the old list and the new movie combined. Crucially, the old state remains unchanged after the operation:

import {expect} from 'chai';

import {List} from 'immutable';

describe('immutability', () => {

// ...

describe('A List', () => {

function addMovie(currentState, movie) {

return currentState.push(movie);

}

it('is immutable', () => {

let state = List.of('Trainspotting', '28 Days Later');

let nextState = addMovie(state, 'Sunshine');

expect(nextState).to.equal(List.of(

'Trainspotting',

'28 Days Later',

'Sunshine'

));

expect(state).to.equal(List.of(

'Trainspotting',

'28 Days Later'

));

});

});

});

The old state would not have remained unchanged if we'd pushed into a regular array! Since we're using an Immutable List instead, we have the same semantics as we had with the number example.

The idea extends to full state trees as well. A state tree is just a nested data structure of Lists, Maps, and possibly other kinds of collections. Applying an operation to it involves producing a new state tree, leaving the previous one untouched. If the state tree is a Map with a key 'movies' that contains a List of movies, adding a movie means we need to create a new Map, where the movies key points to a new List:

import {expect} from 'chai';

import {List, Map} from 'immutable';

describe('immutability', () => {

// ...

describe('a tree', () => {

function addMovie(currentState, movie) {

return currentState.set(

'movies',

currentState.get('movies').push(movie)

);

}

it('is immutable', () => {

let state = Map({

movies: List.of('Trainspotting', '28 Days Later')

});

let nextState = addMovie(state, 'Sunshine');

expect(nextState).to.equal(Map({

movies: List.of(

'Trainspotting',

'28 Days Later',

'Sunshine'

)

}));

expect(state).to.equal(Map({

movies: List.of(

'Trainspotting',

'28 Days Later'

)

}));

});

});

});

This is exactly the same behavior as before, just extended to show that it works with nested data structures too. The same idea holds to all shapes and sizes of data.

For operations on nested data structures such as this one, Immutable provides several helper functions that make it easier to "reach into" the nested data to produce an updated value. We can use one called update in this case to make the code more concise:

function addMovie(currentState, movie) {

return currentState.update('movies', movies => movies.push(movie));

}

This gives us an understanding of how immutable data feels like. It is what we'll be using for our application state. There's a lot of functionality packed into the Immutable API though, and we've only just scratched the surface.

While immutable data is a key aspect of Redux architectures, there is no hard requirement to use the Immutable library with it. In fact, the examples in the official Redux documentation mostly use plain old JavaScript objects and arrays, and simply refrain from mutating them by convention.

In this tutorial, we'll use the Immutable library instead, and there are several reasons for it:

- Immutable's data structures are designed from the ground up to be used immutably and thus provide an API that makes immutable operations convenient.

- I'm partial to Rich Hickey's view that there is no such as thing as immutability by convention. If you use data structures that allow mutations, sooner or later you or someone else is bound to make a mistake and mutate them. This is especially true when you're just getting started. Things like Object.freeze() may help with this.

- Immutable's data structures are persistent, meaning that they are internally structured so that producing new versions is efficient both in terms of time and memory, even for large state trees. Using plain objects and arrays may result in excessive amounts of copying, which hurts performance.

Writing The Application Logic With Pure Functions

Armed with an understanding of immutable state trees and the functions that operate on them, we can turn our attention to the logic of our voting application itself. The core of the app will be formed from the pieces that we have been discussing: A tree structure and a set of functions that produce new versions of that tree structure.

Loading Entries

First of all, as we discussed earlier, the application allows "loading in" a collection of entries that will be voted on. We could have a function called setEntries that takes a previous state and a collection of entries and produces a state where the entries are included. Here's a test for that:

import {List, Map} from 'immutable';

import {expect} from 'chai';

import {setEntries} from '../src/core';

describe('application logic', () => {

describe('setEntries', () => {

it('adds the entries to the state', () => {

const state = Map();

const entries = List.of('Trainspotting', '28 Days Later');

const nextState = setEntries(state, entries);

expect(nextState).to.equal(Map({

entries: List.of('Trainspotting', '28 Days Later')

}));

});

});

});

Our initial implementation of setEntries can just do the simplest thing possible: It can set an entries key in the state Map, and set the value as the given List of entries. That produces the first of the state trees we designed earlier.

export function setEntries(state, entries) {

return state.set('entries', entries);

}

For convenience, we'll allow the input entries to be a regular JavaScript array (or actually anything iterable). It should still be an Immutable List by the time it's in the state tree:

it('converts to immutable', () => {

const state = Map();

const entries = ['Trainspotting', '28 Days Later'];

const nextState = setEntries(state, entries);

expect(nextState).to.equal(Map({

entries: List.of('Trainspotting', '28 Days Later')

}));

});

In the implementation we should pass the given entries into the List constructor to satisfy this requirement:

import {List} from 'immutable';

export function setEntries(state, entries) {

return state.set('entries', List(entries));

}

Starting The Vote

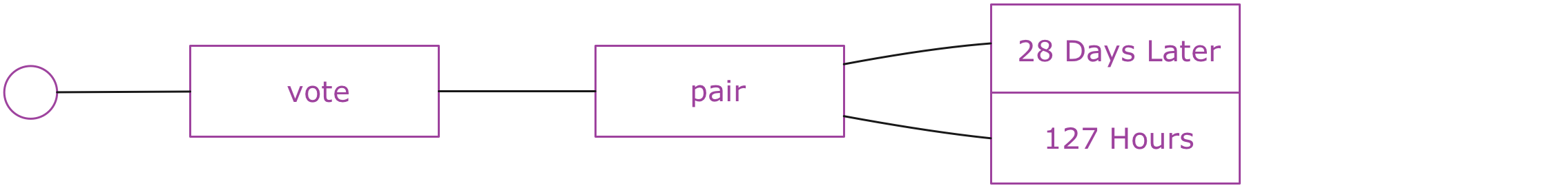

We can begin the voting by calling a function called next on a state that already has entries set. That means, going from the first to the second of the state trees we designed.

The function takes no additional arguments. It should create a vote Map on the state, where the two first entries are included under the key pair. The entries under vote should no longer be in the entries List:

import {List, Map} from 'immutable';

import {expect} from 'chai';

import {setEntries, next} from '../src/core';

describe('application logic', () => {

// ..

describe('next', () => {

it('takes the next two entries under vote', () => {

const state = Map({

entries: List.of('Trainspotting', '28 Days Later', 'Sunshine')

});

const nextState = next(state);

expect(nextState).to.equal(Map({

vote: Map({

pair: List.of('Trainspotting', '28 Days Later')

}),

entries: List.of('Sunshine')

}));

});

});

});

The implementation for this will merge an update into the old state, where the first two entries are put in one List, and the rest in the new version of entries:

import {List, Map} from 'immutable';

// ...

export function next(state) {

const entries = state.get('entries');

return state.merge({

vote: Map({pair: entries.take(2)}),

entries: entries.skip(2)

});

}

Voting

When a vote is ongoing, it should be possible for people to vote on entries. When a new vote is cast for an entry, a "tally" for it should appear in the vote. If there already is a tally for the entry, it should be incremented:

import {List, Map} from 'immutable';

import {expect} from 'chai';

import {setEntries, next, vote} from '../src/core';

describe('application logic', () => {

// ...

describe('vote', () => {

it('creates a tally for the voted entry', () => {

const state = Map({

vote: Map({

pair: List.of('Trainspotting', '28 Days Later')

}),

entries: List()

});

const nextState = vote(state, 'Trainspotting');

expect(nextState).to.equal(Map({

vote: Map({

pair: List.of('Trainspotting', '28 Days Later'),

tally: Map({

'Trainspotting': 1

})

}),

entries: List()

}));

});

it('adds to existing tally for the voted entry', () => {

const state = Map({

vote: Map({

pair: List.of('Trainspotting', '28 Days Later'),

tally: Map({

'Trainspotting': 3,

'28 Days Later': 2

})

}),

entries: List()

});

const nextState = vote(state, 'Trainspotting');

expect(nextState).to.equal(Map({

vote: Map({

pair: List.of('Trainspotting', '28 Days Later'),

tally: Map({

'Trainspotting': 4,

'28 Days Later': 2

})

}),

entries: List()

}));

});

});

});

You could build all these nested Maps and Lists more concisely using the fromJS function from Immutable.

We can make these tests pass with the following:

export function vote(state, entry) {

return state.updateIn(

['vote', 'tally', entry],

0,

tally => tally + 1

);

}

Using updateIn makes this pleasingly succinct. What the code expresses is "reach into the nested data structure path ['vote', 'tally', 'Trainspotting'], and apply this function there. If there are keys missing along the path, create new Maps in their place. If the value at the end is missing, initialize it with 0".

It packs a lot of punch, but this is exactly the kind of code that makes working with immutable data structures pleasant, so it's worth spending a bit of time getting comfortable with it.

Moving to The Next Pair

Once the vote for a given pair is over, we should proceed to the next one. The winning entry from the current vote should be kept, and added back to the end of the entries, so that it will later be paired with something else. The losing entry is thrown away. If there is a tie, both entries are kept.

We'll add this logic to the existing implementation of next:

describe('next', () => {

// ...

it('puts winner of current vote back to entries', () => {

const state = Map({

vote: Map({

pair: List.of('Trainspotting', '28 Days Later'),

tally: Map({

'Trainspotting': 4,

'28 Days Later': 2

})

}),

entries: List.of('Sunshine', 'Millions', '127 Hours')

});

const nextState = next(state);

expect(nextState).to.equal(Map({

vote: Map({

pair: List.of('Sunshine', 'Millions')

}),

entries: List.of('127 Hours', 'Trainspotting')

}));

});

it('puts both from tied vote back to entries', () => {

const state = Map({

vote: Map({

pair: List.of('Trainspotting', '28 Days Later'),

tally: Map({

'Trainspotting': 3,

'28 Days Later': 3

})

}),

entries: List.of('Sunshine', 'Millions', '127 Hours')

});

const nextState = next(state);

expect(nextState).to.equal(Map({

vote: Map({

pair: List.of('Sunshine', 'Millions')

}),

entries: List.of('127 Hours', 'Trainspotting', '28 Days Later')

}));

});

});

In the implementation we'll just concatenate the "winners" of the current vote to the entries. We can find those winners with a new function called getWinners:

function getWinners(vote) {

if (!vote) return [];

const [a, b] = vote.get('pair');

const aVotes = vote.getIn(['tally', a], 0);

const bVotes = vote.getIn(['tally', b], 0);

if (aVotes > bVotes) return [a];

else if (aVotes < bVotes) return [b];

else return [a, b];

}

export function next(state) {

const entries = state.get('entries')

.concat(getWinners(state.get('vote')));

return state.merge({

vote: Map({pair: entries.take(2)}),

entries: entries.skip(2)

});

}

Ending The Vote

At some point there's just going to be one entry left when a vote ends. At that point we have a winning entry. What we should do is, instead of trying to form a next vote, just set the winner in the state explicitly. The vote is over.

describe('next', () => {

// ...

it('marks winner when just one entry left', () => {

const state = Map({

vote: Map({

pair: List.of('Trainspotting', '28 Days Later'),

tally: Map({

'Trainspotting': 4,

'28 Days Later': 2

})

}),

entries: List()

});

const nextState = next(state);

expect(nextState).to.equal(Map({

winner: 'Trainspotting'

}));

});

});

In the implementation of next we should have a special case for the situation where the entries has a size of 1 after we've processed the current vote:

export function next(state) {

const entries = state.get('entries')

.concat(getWinners(state.get('vote')));

if (entries.size === 1) {

return state.remove('vote')

.remove('entries')

.set('winner', entries.first());

} else {

return state.merge({

vote: Map({pair: entries.take(2)}),

entries: entries.skip(2)

});

}

}

We could have just returned Map({winner: entries.first()}) here. But instead we still take the old state as the starting point and explicitly remove 'vote' and 'entries' keys from it. The reason for this is future-proofing: At some point we might have some unrelated data in the state, and it should pass through this function unchanged. It is generally a good idea in these state transformation functions to always morph the old state into the new one instead of building the new state completely from scratch.

Here we have an acceptable version of the core logic of our app, expressed as a few functions. We also have unit tests for them, and writing those tests has been relatively easy: No setup, no mocks, no stubs. That's the beauty of pure functions. We can just call them and inspect the return values.

Note that we haven't even installed Redux yet. We've been able to focus totally on the logic of the app itself, without bringing the "framework" in. There's something very pleasing about that.

Introducing Actions and Reducers

We have the core functions of our app, but in Redux you don't actually call those functions directly. There is a layer of indirection between the functions and the outside world: Actions.

An action is a simple data structure that describes a change that should occur in your app state. It's basically a description of a function call packaged into a little object. By convention, every action has a type attribute that describes which operation the action is for. Each action may also carry additional attributes. Here are a few example actions that match the core functions we have just written:

{type: 'SET_ENTRIES', entries: ['Trainspotting', '28 Days Later']}

{type: 'NEXT'}

{type: 'VOTE', entry: 'Trainspotting'}

If actions are expressed like this, we also need a way to turn them into the actual core function calls. For example, given the VOTE action, the following call should be made:

// This action

let voteAction = {type: 'VOTE', entry: 'Trainspotting'}

// should cause this to happen

return vote(state, voteAction.entry);

What we're going to write is a generic function that takes any kind of action - along with the current state - and invokes the core function that matches the action. This function is called a reducer:

export default function reducer(state, action) {

// Figure out which function to call and call it

}

We should test that the reducer can indeed handle each of our three actions:

import {Map, fromJS} from 'immutable';

import {expect} from 'chai';

import reducer from '../src/reducer';

describe('reducer', () => {

it('handles SET_ENTRIES', () => {

const initialState = Map();

const action = {type: 'SET_ENTRIES', entries: ['Trainspotting']};

const nextState = reducer(initialState, action);

expect(nextState).to.equal(fromJS({

entries: ['Trainspotting']

}));

});

it('handles NEXT', () => {

const initialState = fromJS({

entries: ['Trainspotting', '28 Days Later']

});

const action = {type: 'NEXT'};

const nextState = reducer(initialState, action);

expect(nextState).to.equal(fromJS({

vote: {

pair: ['Trainspotting', '28 Days Later']

},

entries: []

}));

});

it('handles VOTE', () => {

const initialState = fromJS({

vote: {

pair: ['Trainspotting', '28 Days Later']

},

entries: []

});

const action = {type: 'VOTE', entry: 'Trainspotting'};

const nextState = reducer(initialState, action);

expect(nextState).to.equal(fromJS({

vote: {

pair: ['Trainspotting', '28 Days Later'],

tally: {Trainspotting: 1}

},

entries: []

}));

});

});

Our reducer should delegate to one of the core functions based on the type of the action. It also knows how to unpack the additional arguments of each function from the action object:

import {setEntries, next, vote} from './core';

export default function reducer(state, action) {

switch (action.type) {

case 'SET_ENTRIES':

return setEntries(state, action.entries);

case 'NEXT':

return next(state);

case 'VOTE':

return vote(state, action.entry)

}

return state;

}

Note that if the reducer doesn't recognize the action, it just returns the current state.

An important additional requirement of reducers is that if they are called with an undefined state, they know how to initialize it to a meaningful value. In our case, the initial value is a Map. So, giving an undefined state should work as if an empty Map had been given:

describe('reducer', () => {

// ...

it('has an initial state', () => {

const action = {type: 'SET_ENTRIES', entries: ['Trainspotting']};

const nextState = reducer(undefined, action);

expect(nextState).to.equal(fromJS({

entries: ['Trainspotting']

}));

});

});

Since our application's logic is in core.js, it makes sense to introduce the initial state there:

export const INITIAL_STATE = Map();

In the reducer we'll import it and use it as the default value of the state argument:

import {setEntries, next, vote, INITIAL_STATE} from './core';

export default function reducer(state = INITIAL_STATE, action) {

switch (action.type) {

case 'SET_ENTRIES':

return setEntries(state, action.entries);

case 'NEXT':

return next(state);

case 'VOTE':

return vote(state, action.entry)

}

return state;

}

What is interesting about the way this reducer works is how it can be generically used to take the application from one state to the next, given any type of action. Actually, given a collection of past actions, you can actually just reduce that collection into the current state. That's why the function is called a reducer: It fulfills the contract of a reduce callback function.

it('can be used with reduce', () => {

const actions = [

{type: 'SET_ENTRIES', entries: ['Trainspotting', '28 Days Later']},

{type: 'NEXT'},

{type: 'VOTE', entry: 'Trainspotting'},

{type: 'VOTE', entry: '28 Days Later'},

{type: 'VOTE', entry: 'Trainspotting'},

{type: 'NEXT'}

];

const finalState = actions.reduce(reducer, Map());

expect(finalState).to.equal(fromJS({

winner: 'Trainspotting'

}));

});

This ability to batch and/or replay a collection of actions is a major benefit of the action/reducer model of state transitions, when compared to calling the core functions directly. For example, given that actions are just objects that you can also serialize to JSON, you could easily send them over to a Web Worker and run your reducer logic there. Or you can even send them over the network, as we're going to do later!

Note that we are using plain objects as actions instead of Immutable data structures. This is something Redux actually requires us to do.

A Taste of Reducer Composition

Our core functionality is currently defined so that each function takes the whole state of the application and returns the whole, next state of the application.

It is easy to see how keeping to this pattern may not be a good idea in large applications. If each and every operation in the application needs to be aware of the structure of the whole state, things can easily get brittle. If you wanted to change the shape of the state, it would require a whole lot of changes.

It is a much better idea to, whenever you can, make operations work on the smallest piece (or subtree) of the state possible. What we're talking about is modularization: Have the functionality that deals with a given piece of data deal with only that part of the data, as if the rest didn't exist.

Our application is so tiny that we don't have a problem of this kind yet, but we do already have one opportunity to improve on this: There is no reason for the vote function to receive the whole app state, since it only works on the 'vote' part of it. That's the only thing it should know about. We can modify the existing unit tests for vote to reflect this idea:

describe('vote', () => {

it('creates a tally for the voted entry', () => {

const state = Map({

pair: List.of('Trainspotting', '28 Days Later')

});

const nextState = vote(state, 'Trainspotting')

expect(nextState).to.equal(Map({

pair: List.of('Trainspotting', '28 Days Later'),

tally: Map({

'Trainspotting': 1

})

}));

});

it('adds to existing tally for the voted entry', () => {

const state = Map({

pair: List.of('Trainspotting', '28 Days Later'),

tally: Map({

'Trainspotting': 3,

'28 Days Later': 2

})

});

const nextState = vote(state, 'Trainspotting');

expect(nextState).to.equal(Map({

pair: List.of('Trainspotting', '28 Days Later'),

tally: Map({

'Trainspotting': 4,

'28 Days Later': 2

})

}));

});

});

As we see, this also simplifies the test code, which is usually a good sign!

The vote implementation should now just take the vote part of the state, and update its tally:

export function vote(voteState, entry) {

return voteState.updateIn(

['tally', entry],

0,

tally => tally + 1

);

}

Now it becomes the job of our reducer to pick apart the state so that it gives only the relevant part to the vote function:

export default function reducer(state = INITIAL_STATE, action) {

switch (action.type) {

case 'SET_ENTRIES':

return setEntries(state, action.entries);

case 'NEXT':

return next(state);

case 'VOTE':

return state.update('vote',

voteState => vote(voteState, action.entry));

}

return state;

}

This is a small example of the kind of pattern that becomes much more important the larger an application gets: The main reducer function only hands parts of the state to lower-level reducer functions. We separate the job of finding the right location in the state tree from applying the update to that location.

The Redux documentation for reducers goes into these patterns of reducer composition in a lot more detail, and also describes some helper functions that makes reducer composition easier in many cases.

Introducing The Redux Store

Now that we have a reducer, we can start looking at how this all plugs into Redux itself.

As we just saw, if you had a collection of all the actions that are ever going to occur in your application, you could just call reduce. Out pops the final state of your app. Of course, you usually don't have a collection of all those actions. They will arrive spread out over time, as things happen in the world: When users interact with the app, when data is received from networks, or when timeouts trigger.

To deal with this reality, we can use a Redux Store. It is an object that, as the name implies, stores the state of your application over time.

A Redux Store is initialized with a reducer function, such as the one we have just implemented:

import {createStore} from 'redux';

const store = createStore(reducer);

What you can then do is dispatch actions to that Store. The Store will internally use your reducer to apply the actions to the current state, and store the resulting, next state:

store.dispatch({type: 'NEXT'});

At any point in time, you can obtain the current state from inside the Store:

store.getState();

We're going to set up and export a Redux Store in a file called store.js. Let's test it first. We should be able to make a store, read its initial state, dispatch action, and witness the changed state:

import {Map, fromJS} from 'immutable';

import {expect} from 'chai';

import makeStore from '../src/store';

describe('store', () => {

it('is a Redux store configured with the correct reducer', () => {

const store = makeStore();

expect(store.getState()).to.equal(Map());

store.dispatch({

type: 'SET_ENTRIES',

entries: ['Trainspotting', '28 Days Later']

});

expect(store.getState()).to.equal(fromJS({

entries: ['Trainspotting', '28 Days Later']

}));

});

});

Before we can create the Store, we need to add Redux into the project:

npm install --save redux

Then we can create store.js, where we simply call createStore with our reducer:

import {createStore} from 'redux';

import reducer from './reducer';

export default function makeStore() {

return createStore(reducer);

}

So, the Redux store ties things together into something we'll be able to use as the central point of our application: It holds the current state, and over time can receive actions that evolve the state from one version to the next, using the core application logic we have written and exposed through the reducer.

Question: How many variables do you need in a Redux application?

Answer: One. The one inside the store.

This notion may sound ludicrous at first - at least if you haven't done much functional programming. How can you do anything useful with just one variable?

But the fact is we don't need any more variables than that. The current state tree is the only thing that varies over time in our core application. The rest is all constants and immutable values.

It is quite remarkable just how small the integration surface area between our application code and Redux actually is. Because we have a generic reducer function, that's the only thing we need to let Redux know about. The rest is all in our own, non-framework-specific, highly portable and purely functional code!

If we now create the index.js entry point for the application, we can have it create and export a store:

import makeStore from './src/store';

export const store = makeStore();

Since we also export the store, you could now fire up a Node REPL (with e.g. babel-node), require the index.js file and interact with the application using the store.

Setting Up a Socket.io Server

Our application is going to act as a server for a separate browser application that provides the UIs for voting and viewing results. For that purpose, we need a way for the clients to communicate with the server, and vice versa.

This is an app that benefits from real-time communication, since it's fun for voters to see their own actions and those of others immediately when they occur. For that reason, we're going to use WebSockets to communicate. More specifically, we're going to use the Socket.io library that provides a nice abstraction for WebSockets that works across browsers. It also has a number of fallback mechanisms for clients that don't support WebSockets.

Let's add Socket.io to the project:

npm install --save socket.io

Then, let's create a file called server.js which exports a function that creates a Socket.io server:

import Server from 'socket.io';

export default function startServer() {

const io = new Server().attach(8090);

}

This creates a Socket.io server, as well as a regular HTTP server bound to port 8090. The choice of port is arbitrary, but it needs to match the port we'll later use to connect from clients.

We can then have index.js call this function, so that a server is started when the app starts:

import makeStore from './src/store';

import startServer from './src/server';

export const store = makeStore();

startServer();

If we now add a start command to our package.json, we'll make startup a bit simpler:

"scripts": {

"start": "babel-node index.js",

"test": "mocha --compilers js:babel-core/register --require ./test/test_helper.js --recursive",

"test:watch": "npm run test -- --watch"

},

Now we can simply start the server (and create the Redux store) by typing:

npm run start

The babel-node command comes from the babel-cli package that we installed earlier. It allows us to easily run Node code with Babel transpiling support enabled. It adds some performance overhead so it isn't generally recommended for production use, but it works well for the purposes of our tutorial.

Broadcasting State from A Redux Listener

We have a Socket.io server and we have a Redux state container but they aren't yet integrated in any way. The next thing we'll do is change that.

Our server should be able to let clients know about the current state of the application (i.e. "what is being voted on?", "What is the current tally of votes?", "Is there a winner yet?"). It can do so by emitting a Socket.io event to all connected clients whenever something changes.

And how can we know when something has changed? Well, Redux provides something for exactly this purpose: You can subscribe to a Redux store. You do that by providing a function that the store will call after every action it applies, when the state has potentially changed. It is essentially a callback to state changes within the store.

We'll do this in startServer, so let's give it the Redux store first:

import makeStore from './src/store';

import {startServer} from './src/server';

export const store = makeStore();

startServer(store);

What we'll do is subscribe a listener to the store that reads the current state, turns it into a plain JavaScript object, and emits it as a state event on the Socket.io server. The result will be that a JSON-serialized snapshot of the state is sent over all active Socket.io connections.

import Server from 'socket.io';

export function startServer(store) {

const io = new Server().attach(8090);

store.subscribe(

() => io.emit('state', store.getState().toJS())

);

}

We are now publishing the whole state to everyone whenever any changes occur. This may end up causing a lot of data transfer. One could think of various ways of optimizing this (e.g. just sending the relevant subset, sending diffs instead of snapshots...), but this implementation has the benefit of being easy to write, so we'll just use it for our example app.

In addition to sending a state snapshot whenever state changes, it will be useful for clients to immediately receive the current state when they connect to the application. That lets them sync their client-side state to the latest server state right away.

We can listen to 'connection' events on our Socket.io server. We get one each time a client connects. In the event listener we can emit the current state right away:

import Server from 'socket.io';

export function startServer(store) {

const io = new Server().attach(8090);

store.subscribe(

() => io.emit('state', store.getState().toJS())

);

io.on('connection', (socket) => {

socket.emit('state', store.getState().toJS());

});

}

Receiving Remote Redux Actions

In addition to emitting the application state out to clients, we should also be able to receive updates from them: Voters will be assigning votes, and the vote organizer will be moving the contest forward using the NEXT action.

The solution we'll use for this is actually quite simple. What we can do is simply have our clients emit 'action' events that we feed directly into our Redux store:

import Server from 'socket.io';

export function startServer(store) {

const io = new Server().attach(8090);

store.subscribe(

() => io.emit('state', store.getState().toJS())

);

io.on('connection', (socket) => {

socket.emit('state', store.getState().toJS());

socket.on('action', store.dispatch.bind(store));

});

}

This is where we start to go beyond "regular Redux", since we are now essentially accepting remote actions into our store. However, the Redux architecture makes it remarkably easy to do: Since actions are just JavaScript objects, and JavaScript objects can easily be sent over the network, we immediately got a system with which any number of clients can participate in voting. That's no small feat!

There are some obvious security considerations here. We're allowing any connected Socket.io client to dispatch any action into the Redux store.

In most real-world cases, there should be some kind of firewall here, probably not dissimilar to the one in the Vert.x Event Bus Bridge. Apps that have an authentication mechanism should also plug it in here.

Our server now operates essentially like this:

- A client sends an action to the server.

- The server hands the action to the Redux Store.

- The Store calls the reducer and the reducer executes the logic related to the action.

- The Store updates its state based on the return value of the reducer.

- The Store executes the listener function subscribed by the server.

- The server emits a

'state'event. - All connected clients - including the one that initiated the original action - receive the new state.

Before we're done with the server, let's have it load up a set of test entries for us to play with, so that we have something to look at once we have the whole system going. We can add an entries.json file that lists the contest entries. For example, the list of Danny Boyle's feature films to date - feel free to substitute your favorite subject matter though!

[

"Shallow Grave",

"Trainspotting",

"A Life Less Ordinary",

"The Beach",

"28 Days Later",

"Millions",

"Sunshine",

"Slumdog Millionaire",

"127 Hours",

"Trance",

"Steve Jobs"

]

We can just load this in into index.js and then kick off the vote by dispatching a NEXT action:

import makeStore from './src/store';

import {startServer} from './src/server';

export const store = makeStore();

startServer(store);

store.dispatch({

type: 'SET_ENTRIES',

entries: require('./entries.json')

});

store.dispatch({type: 'NEXT'});

And with that, we're ready to switch our focus to the client application.

The Client Application

During the remainder of this tutorial we'll be writing a React application that connects to the server we now have and makes the voting system come alive to users.

We're going to use Redux again on the client. This is arguably the most common use case for Redux: As the underlying engine of a React application. We've already seen how Redux itself works, and soon we'll learn exactly how it fits together with React and how using it influences the design of React apps.

I recommend following the steps and writing the app from scratch, but if you prefer you can get the code from GitHub.

Client Project Setup

Update 2016-08-02: There is now an easier, officially supported way to get going with a React+Webpack+Babel application than the one explained in this guide: The Create React App tool. I encourage you to try it instead of setting up manually as we do here, by following their instructions for getting started.

You will need to eject the tool once we get to hot reloading and unit testing, because those are not supported by the tool at the moment.

The very first thing we're going to do is start a fresh NPM project, just like we did with the server.

mkdir voting-client

cd voting-client

npm init -y

We're going to need an HTML host page for the app. Let's put that in dist/index.html:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<div id="app"></div>

<script src="bundle.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

This document just contains a <div> with id app, into which we'll put our application. It expects there to be a JavaScript file called bundle.js in the same directory.

Let's also create the first JavaScript file for this app. This will be the application's entry point file. For now we can just put a simple logging statement in it:

console.log('I am alive!');

To ease our client development workflow, we're going to use Webpack along with its development server, so let's add both to the project:

npm install --save-dev webpack webpack-dev-server

If you don't have them already, also install the same packages globally so that you'll be able to conveniently launch them from the command line: npm install -g webpack webpack-dev-server.

Next, let's add a Webpack configuration file at the root of the project, that matches the files and directories we've created:

module.exports = {

entry: [

'./src/index.js'

],

output: {

path: __dirname + '/dist',

publicPath: '/',

filename: 'bundle.js'

},

devServer: {

contentBase: './dist'

}

};

This will find our index.js entrypoint, and build everything into the dist/bundle.js bundle. It'll also use the dist directory as the base of the development server.

You should now be able to run Webpack to produce bundle.js:

webpack

You should also be able to start the dev server, after which the test page (including the logging statement from index.js) should be accessible in localhost:8080.

webpack-dev-server

Since we're going to use both ES6 and React's JSX syntax in the client code, we need some tooling for those. Babel knows how to process both, so let's plug it in. We need both Babel itself and its Webpack loader:

npm install --save-dev babel-core babel-loader babel-preset-es2015 babel-preset-react

In package.json we need to enable Babel support for both ES6/ES2015 and React JSX, by activating the presets we have just installed:

"babel": {

"presets": ["es2015", "react"]

}

In the Webpack config file we can now change things so that Webpack will find .jsx files along with .js files, and process both through Babel:

module.exports = {

entry: [

'./src/index.js'

],

module: {

loaders: [{

test: /\.jsx?$/,

exclude: /node_modules/,

loader: 'babel'

}]

},

resolve: {

extensions: ['', '.js', '.jsx']

},

output: {

path: __dirname + '/dist',

publicPath: '/',

filename: 'bundle.js'

},

devServer: {

contentBase: './dist'

}

};

In this tutorial we won't be spending any time on CSS. If you'd like the app to look nicer, you can of course add your own styles as you go along.

Alternatively, you can grab some styling from this commit. In addition to a CSS file, it adds Webpack support for including (and autoprefixing) it, as well as a slightly improved result visualization component.

Unit Testing support

We'll be writing some unit tests for the client code too. We can use the same unit test libraries that we used on the server - Mocha and Chai - to test it:

npm install --save-dev mocha chai

We're going to test our React components as well, and that's going to require a DOM. One alternative would be to run tests in an actual web browser with a library like Karma. However, we don't actually need to do that because we can get away with using jsdom, a pure JavaScript DOM implementation that runs in Node:

npm install --save-dev jsdom

The latest versions of jsdom require io.js or Node.js 4.0.0. If you are running an older Node version, you need to explicitly install an older version: npm install --save-dev jsdom@3

We also need a bit of setup code for jsdom before it's ready for React to use. We essentially need to create jsdom versions of the document and window objects that would normally be provided by the web browser. Then we need to put them on the global object, so that they will be discovered by React when it accesses document or window. We can set up a test helper file for this kind of setup code:

import jsdom from 'jsdom';

const doc = jsdom.jsdom('<!doctype html><html><body></body></html>');

const win = doc.defaultView;

global.document = doc;

global.window = win;

Additionally, we need to take all the properties that the jsdom window object contains, such as navigator, and hoist them on to the Node.js global object. This is done so that properties provided by window can be used without the window. prefix, which is what would happen in a browser environment. Some of the code inside React relies on this:

import jsdom from 'jsdom';

const doc = jsdom.jsdom('<!doctype html><html><body></body></html>');

const win = doc.defaultView;

global.document = doc;

global.window = win;

Object.keys(window).forEach((key) => {

if (!(key in global)) {

global[key] = window[key];

}

});

We're also going to be using Immutable collections, so we need to repeat the same trick we applied on the server to add Chai expectation support for them. We should install both the immutable and the chai-immutable package:

npm install --save immutable npm install --save-dev chai-immutable

Then we should enable it in the test helper file:

import jsdom from 'jsdom';

import chai from 'chai';

import chaiImmutable from 'chai-immutable';

const doc = jsdom.jsdom('<!doctype html><html><body></body></html>');

const win = doc.defaultView;

global.document = doc;

global.window = win;

Object.keys(window).forEach((key) => {

if (!(key in global)) {

global[key] = window[key];

}

});

chai.use(chaiImmutable);

The final step before we can run tests is to come up with the command that will run them, and put it in our package.json. Here it is:

"scripts": {

"test": "mocha --compilers js:babel-core/register --require ./test/test_helper.js \"test/**/*@(.js|.jsx)\""

},

This is almost the same command that we used in the server's package.json. There only difference is in the test file specification: On the server we just used --recursive, but that option won't find .jsx files. We need to use a glob that will find all .js and .jsx test files.

It will be useful to continuously run tests whenever code changes occur. We can add a test:watch command for this. It is identical to the one for the server:

"scripts": {

"test": "mocha --compilers js:babel-core/register --require ./test/test_helper.js 'test/**/*.@(js|jsx)'",

"test:watch": "npm run test -- --watch"

},

React and react-hot-loader

With the Webpack and Babel infrastructure in place, let's talk about React!

What's really cool about the way React applications get built with Redux and Immutable is that we can write everything as so-called Pure Components (also sometimes called "Dumb Components"). As a concept, this is similar to pure functions, in that there are a couple of rules to follow:

- A pure component receives all its data as props, like a function receives all its data as arguments. It should have no side effects, including reading data from anywhere else, initiating network requests, etc.

- A pure component generally has no internal state. What it renders is fully driven by its input props. Rendering the same pure component twice with the same props should result in the same UI. There's no hidden state inside the component that would cause the UI to differ between the two renders.

This has a similar simplifying effect as using pure functions does: We can figure out what a component does by looking at what it receives as inputs and what it renders. There's nothing else we need to know about the component. We can also test it really easily - almost as easily as we were able to test our pure application logic.

If components can't have state, where will the state be? In an immutable data structure inside a Redux store! We've already seen how that works. The big idea is to separate the state from the user interface code. The React components are just a stateless projection of the state at a given point in time.

But, first things first, let's go ahead and add React to the project:

npm install --save react react-dom

We should also set up react-hot-loader. It will make our development workflow much faster by reloading code for us without losing the current state of the app.

npm install --save-dev react-hot-loader

It would be silly of us not to use react-hot-loader, since we'll have an architecture that makes using it really easy. In fact, the creation of both Redux and react-hot-loader are all part of the same story!

We need to make several updates to webpack.config.js to enable the hot loader. Here's the updated version:

var webpack = require('webpack');

module.exports = {

entry: [

'webpack-dev-server/client?http://localhost:8080',

'webpack/hot/only-dev-server',

'./src/index.js'

],

module: {

loaders: [{

test: /\.jsx?$/,

exclude: /node_modules/,

loader: 'react-hot!babel'

}]

},

resolve: {

extensions: ['', '.js', '.jsx']

},

output: {

path: __dirname + '/dist',

publicPath: '/',

filename: 'bundle.js'

},

devServer: {

contentBase: './dist',

hot: true

},

plugins: [

new webpack.HotModuleReplacementPlugin()

]

};

In the entry section we include two new things to our app's entry points: The client-side library of the Webpack dev server and the Webpack hot module loader. These provide the Webpack infrastructure for hot module replacement. The hot module replacement support isn't loaded by default, so we also need to load its plugin in the plugins section and enable it in the devServer section.

In the loaders section we configure the react-hot loader to be used with our .js and .jsx files, in addition to Babel.

If you now start or restart the development server, you should see a message about Hot Module Replacement being enabled in the console. We're good to go ahead with writing our first component.

Writing The UI for The Voting Screen

The voting screen of the application will be quite simple: While voting is ongoing, it'll always display two buttons - one for each of the entries being voted on. When the vote is over, it'll display the winner.

We've been mainly doing test-first development so far, but for the React components we'll switch our workflow around: We'll write the components first and the tests second. This is because Webpack and react-hot-loader provide an even tighter feedback loop for development than unit tests do. Also, there's no better feedback when writing a UI than to actually see it in action!

We've been mainly doing test-first development so far, but for the React components we'll switch our workflow around: We'll write the components first and the tests second. This is because Webpack and react-hot-loader provide an even tighter feedback loop for development than unit tests do. Also, there's no better feedback when writing a UI than to actually see it in action!

Let's just assume we're going to have a Voting component and render it in the application entry point. We can mount it into the #app div that we added to index.html earlier. We should also rename index.js to index.jsx since it'll now contain some JSX markup:

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

import Voting from './components/Voting';

const pair = ['Trainspotting', '28 Days Later'];

ReactDOM.render(

<Voting pair={pair} />,

document.getElementById('app')

);

The Voting component takes the current pair of entries as props. For now we can just hardcode that pair, and later we'll substitute it with real data. The component itself is pure and doesn't care where the data comes from.

The entrypoint filename must also be changed in webpack.config.js:

entry: [

'webpack-dev-server/client?http://localhost:8080',

'webpack/hot/only-dev-server',

'./src/index.jsx'

],

If you start (or restart) webpack-dev-server now, you'll see it complain about the missing Voting component. Let's fix that by writing our first version of it:

import React from 'react';

export default React.createClass({

getPair: function() {

return this.props.pair || [];

},

render: function() {

return <div className="voting">

{this.getPair().map(entry =>

<button key={entry}>

<h1>{entry}</h1>

</button>

)}

</div>;

}

});

This renders the pair of entries as buttons. You should be able to see them in your web browser. Try making some changes to the component code and see how they're immediately applied in the browser. No restarts, no page reloads. Talk about fast feedback!

If you don't see what you expect, check the webpack-dev-server output as well as the console log in your browser's development tools for problems.

Now we can add our first unit test as well, for the functionality that we've got. It'll go in a file called Voting_spec.jsx:

import Voting from '../../src/components/Voting';

describe('Voting', () => {

});

To test that the component renders those buttons based on the pair prop, we should render it and see what the output was. To render a component in a unit test, we can use a helper function called renderIntoDocument, which will be in the React test utilities package that we first need to install:

npm install --save react-addons-test-utils

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

import {

renderIntoDocument

} from 'react-addons-test-utils';

import Voting from '../../src/components/Voting';

describe('Voting', () => {

it('renders a pair of buttons', () => {

const component = renderIntoDocument(

<Voting pair={["Trainspotting", "28 Days Later"]} />

);

});

});

Once the component is rendered, we can use another React helper function called scryRenderedDOMComponentsWithTag to find the button elements we expect there to be. We expect two of them, and we expect their text contents to be the two entries, respectively:

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

import {

renderIntoDocument,

scryRenderedDOMComponentsWithTag

} from 'react-addons-test-utils';

import Voting from '../../src/components/Voting';

import {expect} from 'chai';

describe('Voting', () => {

it('renders a pair of buttons', () => {

const component = renderIntoDocument(

<Voting pair={["Trainspotting", "28 Days Later"]} />

);

const buttons = scryRenderedDOMComponentsWithTag(component, 'button');

expect(buttons.length).to.equal(2);

expect(buttons[0].textContent).to.equal('Trainspotting');

expect(buttons[1].textContent).to.equal('28 Days Later');

});

});

If you run the test now, you should see it pass:

npm run test

When one of those voting buttons is clicked, the component should invoke a callback function. Like the entry pair, the callback function should also be given to the component as a prop.

Let's go ahead and add a unit test for this too. We can test this by simulating a click using the Simulate object from React's test utilities:

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

import {

renderIntoDocument,

scryRenderedDOMComponentsWithTag,

Simulate

} from 'react-addons-test-utils';

import Voting from '../../src/components/Voting';

import {expect} from 'chai';

describe('Voting', () => {

// ...

it('invokes callback when a button is clicked', () => {

let votedWith;

const vote = (entry) => votedWith = entry;

const component = renderIntoDocument(

<Voting pair={["Trainspotting", "28 Days Later"]}

vote={vote}/>

);

const buttons = scryRenderedDOMComponentsWithTag(component, 'button');

Simulate.click(buttons[0]);

expect(votedWith).to.equal('Trainspotting');

});

});

Getting this test to pass is simple enough. We just need an onClick handler on the buttons that invokes vote with the correct entry:

import React from 'react';

export default React.createClass({

getPair: function() {

return this.props.pair || [];

},

render: function() {

return <div className="voting">

{this.getPair().map(entry =>

<button key={entry}

onClick={() => this.props.vote(entry)}>

<h1>{entry}</h1>

</button>

)}

</div>;

}

});

This is generally how we'll manage user input and actions with pure components: The components don't try to do much about those actions themselves. They merely invoke callback props.

Here we switched back to test-first development by writing the test first and the functionality second. I find it's often easier to initially test user input code from tests than through the browser.

In general, we'll be switching between the test-first and test-last workflows during UI development, based on whichever feels more useful at each step.

Once the user has already voted for a pair, we probably shouldn't let them vote again. While we could handle this internally in the component state, we're really trying to keep our components pure, so we should try to externalize that logic. The component could just take a hasVoted prop, for which we'll just hardcode a value for now:

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

import Voting from './components/Voting';

const pair = ['Trainspotting', '28 Days Later'];

ReactDOM.render(

<Voting pair={pair} hasVoted="Trainspotting" />,

document.getElementById('app')

);

We can make this work quite easily:

import React from 'react';

export default React.createClass({

getPair: function() {

return this.props.pair || [];

},

isDisabled: function() {

return !!this.props.hasVoted;

},

render: function() {

return <div className="voting">

{this.getPair().map(entry =>

<button key={entry}

disabled={this.isDisabled()}

onClick={() => this.props.vote(entry)}>

<h1>{entry}</h1>

</button>

)}

</div>;

}

});

Let's also add a little label to the button that the user has voted on, so that it is clear to them what has happened. The label should become visible for the button whose entry matches the hasVoted prop. We can make a new helper method hasVotedFor to decide whether to render the label or not:

import React from 'react';

export default React.createClass({

getPair: function() {

return this.props.pair || [];

},

isDisabled: function() {

return !!this.props.hasVoted;

},

hasVotedFor: function(entry) {

return this.props.hasVoted === entry;

},

render: function() {

return <div className="voting">

{this.getPair().map(entry =>

<button key={entry}

disabled={this.isDisabled()}

onClick={() => this.props.vote(entry)}>

<h1>{entry}</h1>

{this.hasVotedFor(entry) ?

<div className="label">Voted</div> :

null}

</button>

)}

</div>;

}

});

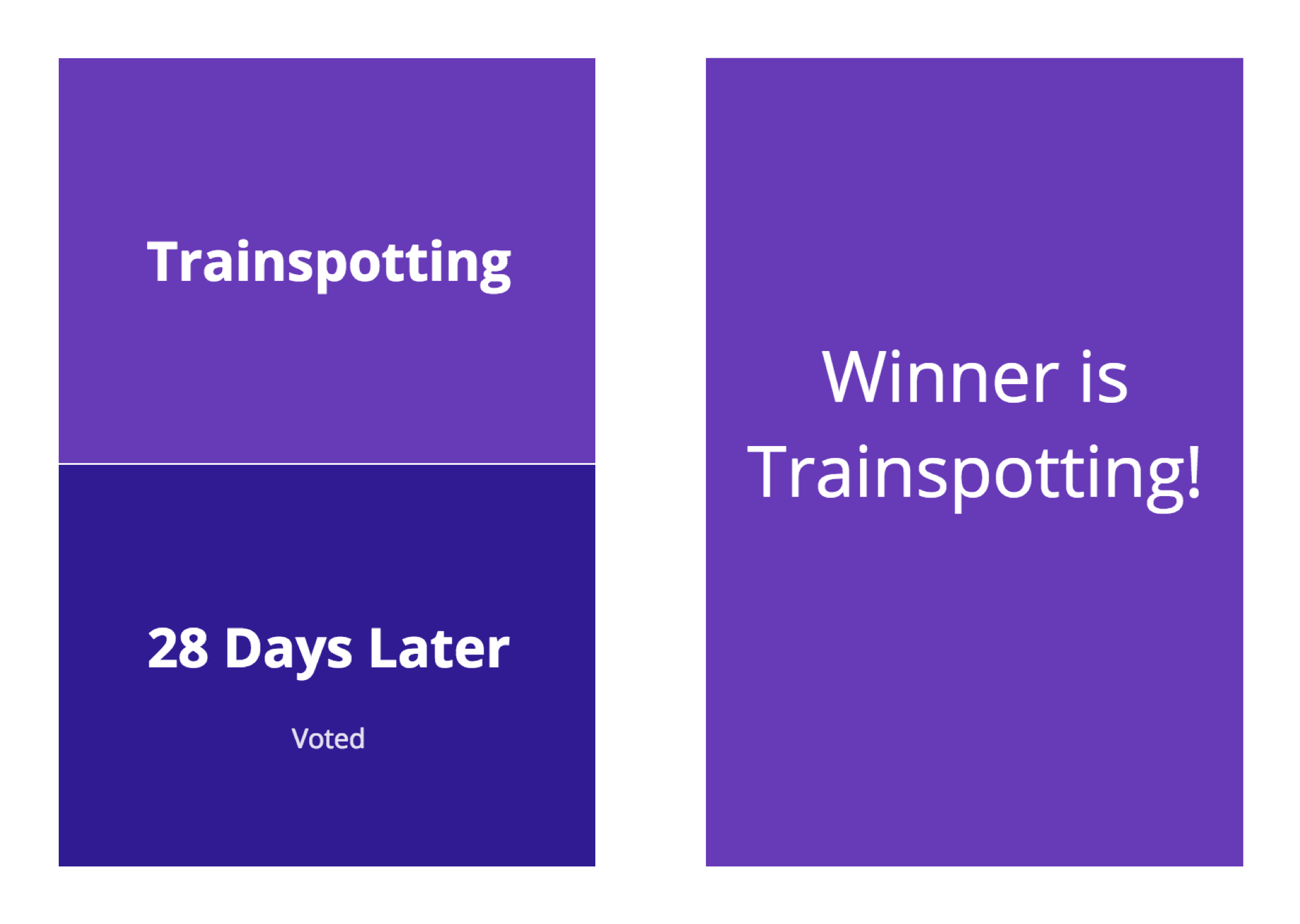

The final requirement for the voting screen is that once there is a winner, it will show just that, instead of trying to render any voting buttons. There might another prop for the winner. Again, we can simply hardcode a value for it temporarily until we have real data to plug in:

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

import Voting from './components/Voting';

const pair = ['Trainspotting', '28 Days Later'];

ReactDOM.render(

<Voting pair={pair} winner="Trainspotting" />,

document.getElementById('app')

);

We could handle this in the component by conditionally rendering a winner div or the buttons:

import React from 'react';

export default React.createClass({

getPair: function() {

return this.props.pair || [];

},

isDisabled: function() {

return !!this.props.hasVoted;

},

hasVotedFor: function(entry) {

return this.props.hasVoted === entry;

},

render: function() {

return <div className="voting">

{this.props.winner ?

<div ref="winner">Winner is {this.props.winner}!</div> :

this.getPair().map(entry =>

<button key={entry}

disabled={this.isDisabled()}

onClick={() => this.props.vote(entry)}>

<h1>{entry}</h1>

{this.hasVotedFor(entry) ?

<div className="label">Voted</div> :

null}

</button>

)}

</div>;

}

});

This is the functionality that we need, but the rendering code is now slightly messy. It might be better if we extract some separate components from this, so that the Voting screen component renders either a Winner component or a Vote component. Starting with the Winner component, it can just render a div:

import React from 'react';

export default React.createClass({

render: function() {

return <div className="winner">

Winner is {this.props.winner}!

</div>;

}

});

The Vote component will be pretty much exactly like the Voting component was before - just concerned with the voting buttons:

import React from 'react';

export default React.createClass({

getPair: function() {

return this.props.pair || [];

},

isDisabled: function() {

return !!this.props.hasVoted;

},

hasVotedFor: function(entry) {

return this.props.hasVoted === entry;

},

render: function() {

return <div className="voting">

{this.getPair().map(entry =>

<button key={entry}

disabled={this.isDisabled()}

onClick={() => this.props.vote(entry)}>

<h1>{entry}</h1>

{this.hasVotedFor(entry) ?

<div className="label">Voted</div> :

null}

</button>

)}

</div>;

}

});

The Voting component itself now merely makes a decision about which of these two components to render:

import React from 'react';

import Winner from './Winner';

import Vote from './Vote';

export default React.createClass({

render: function() {

return <div>

{this.props.winner ?

<Winner ref="winner" winner={this.props.winner} /> :

<Vote {...this.props} />}

</div>;

}

});

Notice that we added a ref for the Winner component. It's something we'll use in unit tests to grab the corresponding DOM node.

That's our pure Voting component! Notice how we haven't really implemented any logic yet: There are buttons but we haven't specified what they do, except invoke a callback. Our components are concerned with rendering the UI and only that. The application logic will come in later, when we connect the UI to a Redux store.

Before we move on though, time to writes some more unit tests for the new features we've added. Firstly, the presence of the hasVoted props should cause the voting buttons to become disabled:

it('disables buttons when user has voted', () => {

const component = renderIntoDocument(

<Voting pair={["Trainspotting", "28 Days Later"]}

hasVoted="Trainspotting" />

);

const buttons = scryRenderedDOMComponentsWithTag(component, 'button');

expect(buttons.length).to.equal(2);

expect(buttons[0].hasAttribute('disabled')).to.equal(true);

expect(buttons[1].hasAttribute('disabled')).to.equal(true);

});

A 'Voted' label should be present on the button whose entry matches the value of hasVoted:

it('adds label to the voted entry', () => {

const component = renderIntoDocument(

<Voting pair={["Trainspotting", "28 Days Later"]}

hasVoted="Trainspotting" />

);